On this day 695 years ago, Thomas of Lancaster, cousin to Edward II came to a grisly end outside the walls of his castle at Pontefract. Here is his dramatic life story and that all important game changing execution. Lancaster’s death, coming after the surrender and imprisonment of the Mortimers and the violent death of Humphrey de Bohun at Boroughbridge saw the end of the rebellion of the Marcher lords and consolidated Edward II’s grip of total power on the throne, and Hugh Despenser the Younger’s grip of power on Edward himself.

This article also appears on Stephen’s blog ‘fourteenthcenturyfiend.’

Thomas of Lancaster, a man of royal birth and immense wealth, power and position, met a grisly end on this day, 22 March 1322; 695 years ago. He was not killed in battle, died of plague or old age, but rather on the order of his cousin King Edward II, Thomas was executed outside the walls of his own castle at Pontefract on a cold, snowy morning. His death marked a critical point in the reign of his royal cousin and one from which both men would be forever marked.

Thomas was born in 1278, some six years prior to Edward II whose birth was on 25 April 1284. Thomas’ father Edmund, was the brother of Edward I meaning that Thomas was a grandson of Henry III (r.1216-1272), nephew to Edward I (r.1272-1307) and first cousin to Edward II. His mother was Blanche of Navarre. Thomas’ half-sister Joan was wife to Philip IV of France, who in turn was the mother of Isabella of France, Edward II’s future queen.(1) In short, Thomas was a well connected man to some of the most powerful and influential royal families in medieval Europe. In 1296, he inherited the vast estates of his father Edmund Crouchback, which included the earldoms of Lancaster, Leicester and Derby. Overnight he had become a rich and powerful man in his own right. Lancaster’s later marriage to Alice de Lacy, daughter of the stalwart friend of Edward I, the earl of Lincoln, would eventually bring Thomas two further earldoms of Lincoln and Salisbury. It was a significant conglomeration of power not seen in England for generations. Used wisely, Thomas could be a great supporter to the crown, but from a position of opposition, his wealth and power could, and would, prove dangerous to his king.

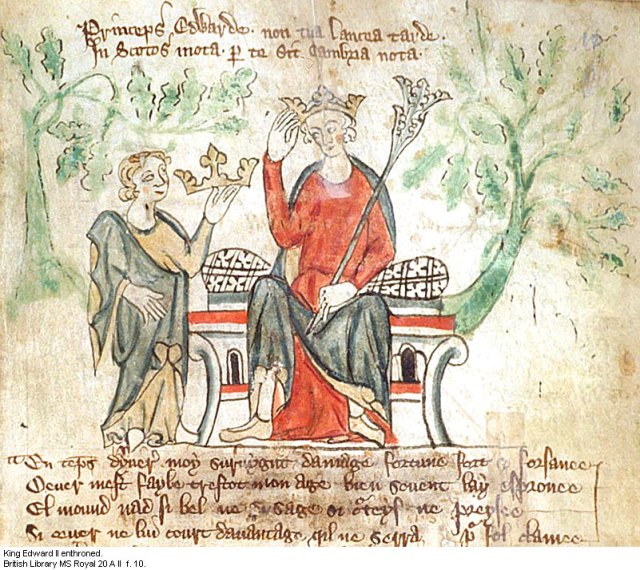

Edward II ascends the throne

Upon Edward II’s accession on 7 July 1307, Lancaster’s allegiances quickly transferred from his deceased uncle Edward I to his cousin and new overlord Edward II. They knew each other well. Thomas and his brother Henry were frequent visitors to Edward’s court when he was Prince of Wales, and Thomas was also a companion to the prince during the various campaigns undertaken as part of Edward I’s Scottish wars. Lancaster saw from the start the growing affection Edward had towards Piers Gaveston since 1300, showing no recorded signs of disaffection prior to 1308. The earl supported Gaveston’s return from his first exile in 1307, his initial elevation to the earldom of Cornwall and his subsequent marriage to Margaret de Clare, sister of the earl of Gloucester all in the same year. In fact, even when the magnates of England were forming in opposition to Gaveston and presented themselves to Edward at the Westminster parliament of April 1308 demanding Gaveston’s exile and threatening a withdrawal of their oaths, Lancaster stood by the king.(2) Yet shortly after, Edward and his cousin quarrelled and from then on in, the two men grew apart and Lancaster quickly sided with Edward’s enemies.

From 1308 until 1312, Thomas became one of Edward II’s leading opponents as Lancaster sought to reduce the influence of Edward’s favourite Piers Gaveston. Coupled with this, by 1310 the magnates of England, long held in check by the late king, were desperate for reform to royal household government and sought to establish restraints on the crown, which of course were framed against their own self-interest. Edward II was caught between two competing demands which became entangled, settling around the permanent exile of Gaveston. In short, one was seen in the same light as the other. Lancaster, along with his father-in-law the earl of Lincoln and the archbishop of Canterbury, led the field in attempting to force upon the king the Ordinances, a set of legislation designed to enact reform and place Edward into some kind of constitutional straight jacket. Clause twenty was highly personal and demanded the removal and permanent exile of Gaveston.(3) The Ordinances became Lancaster’s calling card for the rest of his life. When Piers Gaveston was recalled by the king during his third exile in 1312, it was Lancaster who headed the coalition to bring the earl of Cornwall to account, falling back on the Ordinances as justification for their action despite Edward overturning them weeks after Gaveston’s return to England.

The platform of resistance however, became something far more violent and unconventional than perhaps was originally intended. In June 1312, Gaveston was seized by the earl of Warwick and taken to his castle where Lancaster, Hereford, Warwick and others held a mock trial in which Gaveston was not allowed to speak in order to raise a defence. Being found guilty of treason, Piers was hauled from Warwick castle the following day and taken to Blacklow Hill, on Lancaster’s estates, and there barbarously run through the stomach by one Welshman whilst another eventually cut off his head.(4)

The murder of Edward II’s lover was a tumultuous event that shocked contemporaries. Its barbarity was unconventional. This was clear to those who had committed the crime, so Lancaster as the premier earl in England who had up until now led the opposition, took responsibility for the deed, made plain by the deliberate choice of location for the murder. From here on in, Edward II and his cousin would remain perpetually divided. Edward’s desire for revenge and Lancaster’s uneasy suspicion of the king’s motives, meant their relationship became one characterised by mutual hatred.

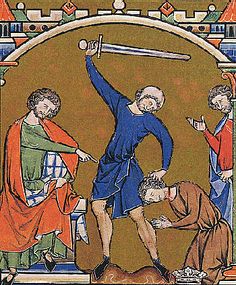

Lancaster took responsibility for the brutal murder of Piers Gaveston in 1312

The following ten years were spent by Lancaster in uneasy opposition. The earl was by character stubborn, obstinate and irascible. Lancaster held to the Ordinances demanding that Edward after 1314 uphold them whilst Edward did everything he could to avoid them. Thomas failed to turn up for the Scottish campaign in 1314 which resulted in the dramatic defeat of the king’s forces at Bannockburn, although defeat in itself was not due to Lancaster’s lack of participation. Yet from 1315 until 1319 when Edward II’s England was beset by problems of famine, Scottish raids into the northern Marches and limited finances, the king commanded an overall uneasy unity amongst his magnates. Lancaster, who had temporarily sidelined a major portion of royal power by becoming head of a new council during the Lincoln Parliament in 1316, soon exposed his weakness.(5) In short, he had no aptitude for government and once he was in a position to enact reform, the earl quickly found he did not understand nor was capable of achieving what he had long since demanded. Shouting about the Ordinances was one thing, but once he had them, enacting change was too arduous for him. He lost credibility, and after the death of the earl of Warwick the year previously, those around him quickly began to see Lancaster for what he was; a bully, who was motivated by self-interest and a seeming desire for power. The rest of Lancaster’s peers baulked at his arrogance, preferring to keep loyal to Edward who was after all their natural king. For many, there was no other choice. Lancaster retired to his estates and there loomed like a angry shadow in the north striking out whenever he felt the need to provoke.

Pontefract Castle was Lancaster’s favourite residence

Edward too played the same game. At court, and surrounded by royal favourites such as Roger Damory, Hugh Audley the Younger, William Montacute and the Despensers, Edward allowed defamatory accusations to run wild, claiming the earl was a traitor. Lancaster struck back attacking Roger Damory’s lands and castles which had to be temporarily transferred into Edward’s hands to avoid outright civil war.(6) The royal favourites meddled further and planned with the earl of Surry to abduct Lancaster’s wife, Alice de Lacy, who was now estranged from her husband. The event took place on 9 May 1317.(7) For a scheme such as this Edward must have known of their plans. Their marriage which had brought Lancaster so much power had broken down early and they never had any children as a result, meaning the earl never fathered a legitimate direct heir. Thomas was outraged by the abduction of his wife, who it was later revealed was likely complicit in the debacle. The whole affair only succeeded in deepening the rift between himself and the king.

In revenge, Thomas opened up and violently pursued a personal grievance against the earl of Surrey which Edward was virtually powerless to stop. When in February 1317, Edward and Isabella’s friend, and the queen’s candidate, Louis de Beaumont was elected as bishop of Durham over Lancaster’s candidate John de Kinardesey, the earl later retaliated by abducting Louis and his brother Henry on the way to the former’s consecration as bishop south of Durham. Rather humiliating for Lancaster, travelling with them were two papal cardinals who were unwittingly caught up by events and taken as hostages: their capture provoked international outrage. Thomas immediately came to their rescue under the pretence that he knew nothing about the incident. The damage to his reputation through implication and to that of Edward’s who failed to protect international papal envoys in his own country, was most certainly felt by both men.(8) England was on the verge of collapse as these two cousins fought in whatever way they could to out manoeuvre each other excepting outright civil war.

Edward was twice jeered by Lancaster’s garrison at Pontefract in 1317 & 1320 as he passed from north to south

Outright conflict was a dangerous game. In 1317 as Edward marched north to see off the most recent threat posed by Scottish raids in the north, Lancaster blockaded the bridges once Edward passed claiming he had the right to be informed about the movement of armed men as he was the hereditary Steward of England. It was a spurious claim and clearly aimed at provoking Edward into open confrontation. Twice in 1317 and again in 1320 Lancaster’s garrison jeered Edward from the walls of Lancaster’s mighty fortress, Pontefract castle, as the king travelled from north to south which almost brought the kingdom to ruin had Edward challenged back. On one of these occasions, the king was narrowly restrained by the earl of Pembroke, who through quick thinking, averted disaster. For Lancaster to oppose Edward openly and in arms with banners unfurled, constituted treason which would certainly result in exile or life imprisonment, as was the long established custom of the time. For Edward, taking on his over-mighty cousin who could command vast forces of men meant if he lost, he too could end up a prisoner as Lancaster sought to take the throne for himself. The stakes were great and so between 1314 -1321 the two men often clashed, sought to undermine each other through those around them and generally thwart each other’s actions. In the end neither had quite the strength or appetite or were held back by those more moderate about them, to gain the upper hand. The net effect was an exhausted stalemate which weakened internal English unity and emboldened the Scots after Bannockburn to take the cause of Scottish independence to northern England in successive and increasingly violent raids. This only became worse, when the briefly patched up relationship between Edward and Lancaster outlined by the Treaty of Leake in 1318 fell apart at the siege of Berwick in the following year.(9) With it the hope of winning in Scotland disappeared to.

As the Marcher lords began their violent rebellion in Glamorgan in 1321 and sought to bring abut the exile of the Despensers, Edward II’s now firmly ensconced royal favourites, Lancaster acted with uncharacteristic caution. Rather than join the rebel lords in the Welsh march where he to held lands, instead Lancaster held meetings, firstly at Sherburn and latterly at Doncaster seeking to test the water of opposition and perhaps bring about a coalition of northern and Welsh barons. In the end it came to nothing as the northern lords preferred to stay out of affairs that did not impact on them. Yet as Edward II fought back in the autumn of 1321 against those who had opposed him in rebellion earlier in the year, Lancaster could not help but take the bait.

He made a fateful error. Rather than ride to the rescue of the besieged barons Rogers Mortimer of Chirk and Wigmore at Shrewsbury in January 1322, Lancaster turned his attention instead to besieging Edward II’s castle at Tickhill near Doncaster whose royal garrison had long kept an eye on the earl’s movements.(10) It was a futile gesture as Edward had ensured the castle was ready for any such attack. With Lancaster occupied, rebel unity crumbled and before long Thomas was embroiled with helping the earl of Hereford as well as the king’s former favourites, Roger Damory and Hugh Audley the Younger, who were previously Lancaster’s enemies. For once he swallowed his pride and now appeared to throw in his lot and challenge the king directly.

Lancaster attempted to take Edward’s castle at Tickhill nr Doncaster but failed

Yet on 1 March 1322, everything changed when William Melton, the archbishop of York, came into possession of letters that had been exchanged between the Scottish Sir James Douglas and a so called ‘King Arthur’.(11) There was no doubt as to who this mysterious King Arthur was: Lancaster. Edward immediately ordered the publication of the letters and any support that Lancaster could have relied on began to quickly fall away as those around him were disgusted by his collusion with the national enemy. Lancaster’s most reliable and loyal retainer Sir Robert Holland deserted the earl in his hour of need, and instead crossed over to Edward’s side. Others quickly followed suit. As the king’s army closed in from the south, Lancaster, Hereford and others attempted to block Edward’s crossing at Burton-on-Trent where Lancaster fatefully unfurled his banner. He and all those in his company were now treasonous rebels. There was no going back. As the royal forces found a crossing, Lancaster and the others retreated to his castle at Pontefract. There angry exchanges took places between the rebels, and only when Roger Clifford drew a dagger on Lancaster, could the earl be persuaded to flee to Northumberland rather than attempt to make a final stand and head off the king.(12)

They did not get far. On 16 March, as Edward’s army continued to move up from the south, Lancaster, Hereford and others were suddenly halted at Boroughbridge by the arrival of Edward’s second army of approximately 4,000 men under the command of Sir Andrew Harclay, sheriff of Cumberland who had already secured the bridge.(13)The rebels divided their forces with Lancaster attempting to ford the crossing, whilst Hereford and his retinue attempted to walk across the bridge fighting to break through Harclay’s lines. It was a fateful error as some of Harclay’s men positioned under the bridge were able to thrust up pikes between gaps in the planks, skewering the earl Hereford and others to death.(14) The following day, despite attempting to bribe Harclay to let him pass, Lancaster and the rebels were taken and there transported to York castle and then onto Pontefract, which had fallen to Edward. Upon his arrival on 21 March, the earl was ‘contemptuously insulted…to his face with malicious and arrogant words’ by the king and the recently returned Despensers.(15)

On 22 March, Lancaster faced the trial of his lifetime. Having been kept overnight in a tower once said to have been built by him to house an imprisoned Edward if ever he had been given the chance, Thomas was brought before his jury made up of his cousin the king, the Despensers, the earls of Pembroke, Kent (also Thomas’ cousin), Richmond, Arundel, Angus and Atholl, along with the royal justice Robert Mablethorp. Last on the jury was Lancaster’s much hated enemy the earl of Surrey, who had in 1317 abducted Thomas’ wife. (16) As accusations were read out against him which included seizing the king’s jewels and horses in 1312 at Newcastle when the earl pursued Edward and Gaveston; bringing armed men to parliaments to threaten the king into a course of action; the siege of Edward’s castle at Tickhill; treasonable correspondence with the Scots and for allowing his garrison to jeer and provoke the king twice from the walls of the very castle in which they now sat, were shamefully read out.(17) The list went on.

During the trial Lancaster was not allowed to speak or ask anyone else to raise a defence on his behalf. It was a clear nod to the treatment Piers Gaveston had received at Warwick castle on 18 June 1312 during his mock trial. In front of his peers, Lancaster was judged guilty on all accounts and breaking with convention of the time, the earl was spectacularly sentenced by the king to death rather than lifetime imprisonment or perpetual exile. He was to be drawn, hanged and then quartered, but in reverence to his royal blood, he would be beheaded only, which it may be said was a result of the intercession of Queen Isabella who herself was at Pontefract with the king.

Lancaster is executed. His head is severed by two or three blows of a sword

There was no delay in the dispatch. Possibly after watching six other rebels receive execution outside the walls of Pontefract, Lancaster following his trial was led out whilst mounted on a mule to meet Edward’s judgement. There in front of the assembled crowd which no doubt included the king and Lancaster’s jury, the earl was forced to kneel facing north towards Scotland; a symbolic reminder of his treason. There he stretched out his head which was subsequently cut off in two or three blows with a sword.(18)

In that moment something fundamental happened. From here on in opposition to the crown, and Edward II in particular was now a dangerous, all-consuming affair. Should anyone wish to challenge the king or his policies which was previously a right of the nobility, they now risked the ultimate penalty. Lancaster had begun the precedent with the murder of Piers Gaveston in 1312, but this itself was murder and beyond the law. By 1322, Edward II by choosing to execute Lancaster through a legal but dubious process, was changing the law to suit his needs and this set a dangerous and far reaching precedent both for future generations, but more pertinently for Edward himself. Future opposition now meant removing the king because if it failed, the king could and would destroy utterly his enemies. This precedent paved the way to Edward’s own deposition in January 1327.

Notes

(1) Vita, 28-29. Maddicott, 2-3

(2) Maddicott, 86-87. Phillips, Seymour. Edward II, 148

(3) English Historical Documents, 532

(4) Vita, 46-9. Gesta Edwardi, 39, 43-4. Ann Londonienses, 207. Trokelowe, 77

(5) Vita, 69. Maddicott, 190

(6) CPR, 1317-21, 34, 46, 58

(7) Trivet, 20-1. Historia Anglicana, 148. Melsa, 335

(8) Trivet, 33. Melsa, 334

(9) Vita, 97-99. Flores, 188. Historia Anglicana, 155. Melsa, 336. Gesta Edwardi, 57

(10) Vita, 121. Lanercost, 231. Anonimalle, 105

(11) CCR, 1318-23, 525-6. Foedera, II, 463, 472, 474. Ann Paulini, 302

(12) Brut, 217

(13) Vita, 124. Ann Paulini, 302. flores, 205

(14) Lanercost, 233. Anonimalle, 107

(15) Anonimalle, 107

(16) Vita, 125. Ann Paulini, 302. Flores, 347

(17) Foedera, II, 478-9

(18) Vita, 126. Flores, 347. Ann Paulini, 303. Gesta Edwardi, 76

Images

Featured: BL Add MS 42130- Execution of Thomas of Lancaster

One: BL MS Royal 20 A f 10 – Edward II ascends the throne:

Two: Execution of kneeling man

Three: Pontefract Castle in it’s heyday prior to to it’s slighting after the civil war in the seventeenth century.

Four: A king threatened by castle garrison

Five: BL MS Royal 10 E iv – A castle under siege

Six: A battle by a river

Seven: BL Add MS 42130 – Execution of Thomas of Lancaster

Facebook: fourteenthcenturyfiend

Twitter: @SpinksStephen